Deja vu? Then, U.S. interference favoured Pearson’s Liberals. Today, China’s interference favours Trudeau’s Liberals

Held on April 8, 1963, Canada’s 26th federal election was notable for two things. It ended John Diefenbaker’s nearly six years as prime minister, thus bringing the Liberals back to office for another extended run. And in a foretaste of current controversy, a foreign government interfered.

Held on April 8, 1963, Canada’s 26th federal election was notable for two things. It ended John Diefenbaker’s nearly six years as prime minister, thus bringing the Liberals back to office for another extended run. And in a foretaste of current controversy, a foreign government interfered.

Like the later elections of 2019 and 2021, the interfering intent was to benefit the Liberals. But the 1963 perpetrator was the United States, not China.

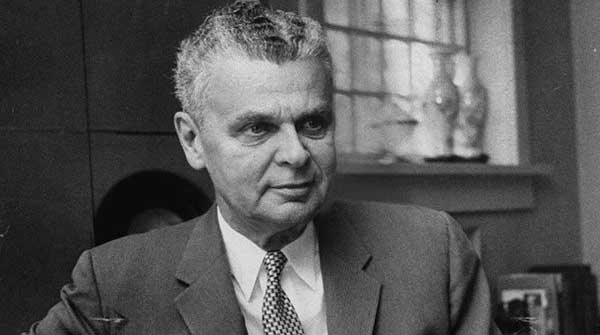

John Diefenbaker was born in 1895 Ontario and raised in Saskatchewan. Although a lawyer by profession, his real passion was politics, which he pursued with a fiery platform style and a decidedly populist touch. After several failed tries, he acceded to the federal Progressive Conservative leadership in 1956.

Then, in the following year’s general election, Diefenbaker ended a Liberal governing run that had started in 1935. But it was just a minority win; the real moment of glory came on March 31, 1958.

|

| Related Stories |

| Canada needs another Diefenbaker

|

| Canada’s first political sex scandal was really a dud

|

| Meddling in other countries’ elections isn’t always outrageous

|

In a campaign dominated by rhetoric proclaiming his “vision of northern development” and the virtues of “unhyphenated Canadianism,” Diefenbaker swept his opposition aside. The Liberal Toronto Star was disdainful – “Humbug and flapdoodle served up with an evangelistic flourish” – but Diefenbaker was triumphant, winning 208 seats (out of 265) and taking almost 54 per cent of the popular vote. Only the wartime 1917 Conservatives ever took a bigger vote share.

Diefenbaker governed as a Red Tory, albeit not always as an adept one. Domestically, he increased the old-age pension, appointed Canada’s first female cabinet minister, extended the federal franchise to all Natives, introduced an (ineffectual) Bill of Rights, and pioneered Canadian wheat sales to China. In foreign policy, he was a significant player in the evolution of the Commonwealth, including a key role in forcing apartheid South Africa out.

But Canadian-American relations were a different matter, with a wary Diefenbaker forever sensitive to any perceived infringements on Canadian sovereignty. And things really went south with John F. Kennedy. Personally, the two men never hit it off. Indeed, they came to quickly despise each other.

There were also substantive differences with regard to foreign policy.

Kennedy wanted Canada to join the Organization of American States and Diefenbaker resisted. Diefenbaker’s hesitation in putting Canada’s military on a war footing during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis rankled with Kennedy. So, too, did Diefenbaker’s reluctance to arm Canada’s Bomarc missiles with nuclear warheads.

The meddling took several forms, all of which served to favour Lester Pearson’s Liberals.

One was the clandestine involvement of Lou Harris, Kennedy’s personal pollster. In an era where political opinion research was in its infancy, Harris was considered state-of-the-art. When he showed up in Canada to instruct the Liberals in the political uses of sophisticated polling, it was with Kennedy’s explicit blessing. In fact, Harris travelled to Canada under a fake passport provided by contacts in the U.S. government.

The American campaign to take Diefenbaker down wasn’t confined to the Harris play. The U.S. embassy, for instance, ran a steady stream of anti-Diefenbaker media briefings and McGeorge Bundy, Kennedy’s national security adviser, subsequently claimed that a State Department rebuttal of a Diefenbaker parliamentary speech had effectively “toppled” the government.

John English, the former Liberal MP and friendly biographer of both Pearson and Pierre Trudeau, believes that Kennedy’s intervention had an impact. And he’s also unequivocal about the rights and wrongs of it: “An American president should not interfere in Canadian elections. And there’s no doubt that Kennedy did, and he did not treat a Canadian prime minister appropriately.”

However, figuring out whether Kennedy was the determining factor is another matter. Diefenbaker had accumulated problems of his own making. Plenty of them.

By the early 1960s, the bright shine of 1958 was seriously tarnished. The visionary rhetoric had come to resemble bombast, the petty side of Diefenbaker’s character had become more evident, and internal party disunity extended to his own cabinet.

And there was the feud with Bank of Canada governor James Coyne. Painfully played out in public and culminating with the governor’s resignation, the affair included a verbal war in which Coyne accused Diefenbaker of acting with “unbridled malice and vindictiveness.”

Still, Diefenbaker’s contest with Kennedy could be described as a gross mismatch that did him no good.

Whereas the American president was very popular in Canada and viewed by many as the handsome and glamorous epitome of what a modern politician should be, Diefenbaker was increasingly perceived as a cranky, fusty relic.

Mismatches of that nature rarely end up well for the underdog.

Troy Media columnist Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps a little bit.

For interview requests, click here.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.