The Duel: Diefenbaker, Pearson, and the Making of Modern Canada delves into the significant moments of their political careers

Serious books on mid-to-late-20th century Canadian politics tend to be relatively thin on the ground. But within a period of 12 months or so, we’ve had two to savour.

Serious books on mid-to-late-20th century Canadian politics tend to be relatively thin on the ground. But within a period of 12 months or so, we’ve had two to savour.

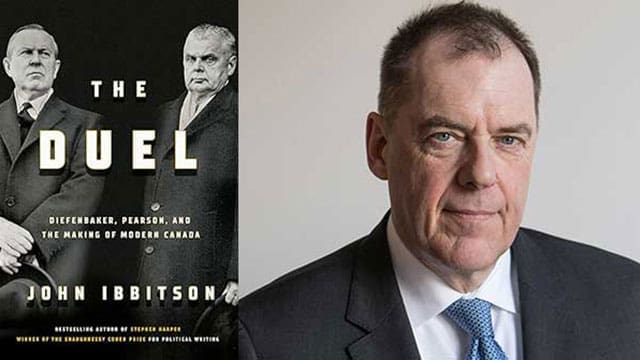

Steve Paikin was first off the mark with his very readable biography of John Turner (see January 12 and January 22 columns). And he’s now joined by John Ibbitson’s The Duel: Diefenbaker, Pearson, and the Making of Modern Canada.

Between 1958 and 1965, Progressive Conservative John Diefenbaker and Liberal Lester Pearson faced off as party leaders in four federal elections. They each won twice, but only Diefenbaker scored a majority. That came in 1958 when he netted 208 seats (out of 265) and an astonishing 54 percent of the popular vote.

|

| Related Stories |

| Unlikely Insider chronicles Jack Austin’s journey from humble beginnings to political success

|

| The Canadian who helped tame America’s Wild West

|

| Pierre Trudeau’s last rollercoaster ride

|

But after 1958, Diefenbaker’s trajectory was consistently negative. In his last time at bat (November 1965), 97 seats and 32 per cent of the vote was the best he could do. Politically, he was a dead man walking.

Historians have generally been much kinder to Pearson than to Diefenbaker, and Ibbitson doesn’t quarrel with the bottom line of that assessment. However, he adds nuance that goes some way towards rehabilitating Diefenbaker’s comparative reputation.

Rather than exclusively focusing on the differences between Pearson and Diefenbaker, Ibbitson notes the degree of continuity. While they may have been chalk and cheese in personality terms, their policies had much in common. Indeed, Ibbitson goes further, in some cases extending the continuity back to Louis St. Laurent, the long-serving Liberal prime minister defeated by Diefenbaker in 1957 and subsequently replaced as Liberal leader by Pearson.

“The Pearson government implemented universal public health care in response to a royal commission launched by the Diefenbaker government. The Diefenbaker government established universal public hospital care in response to legislation passed but not implemented by the St. Laurent government. All three prime ministers share in the achievement of establishing, implementing, and refining equalization. The St. Laurent government decided to cancel the Avro Arrow project; the Diefenbaker government took the blame in implementing the decision.”

But one thing on which they were diametrically opposed was the subject of replacing the Red Ensign with a new Canadian flag.

It had been a goal of Pearson’s for a long time. The demographics of Canada had changed; millions of Canadians had no historic connection to Britain, and the presence of the Union Jack in the ensign’s upper left was an anachronism detracting from national identity.

Diefenbaker very much begged to differ, accusing Pearson of “trying to separate this nation from the past.” For him, it was a hugely emotional issue and he wanted a referendum. He didn’t get one.

After an acrimonious debate that spilled over into everyday life, Pearson’s flag legislation was passed in the early hours of December 15, 1964, and the Red Ensign was officially lowered the following February. Ibbitson’s recounting of the new flag’s raising is pungent: “John Diefenbaker wouldn’t look at it. He lowered his head and wept.”

Interestingly, both men had difficulties with American presidents. It was John F. Kennedy for Diefenbaker and Lyndon Johnson for Pearson.

Diefenbaker’s difficulty was particularly problematic. He and Kennedy had quickly come to despise each other, in addition to which there were substantive foreign policy differences around things like Diefenbaker’s reluctance to arm Canada’s Bomarc missiles with nuclear warheads. So Kennedy set out to undermine Diefenbaker politically – in effect, meddling in the federal elections of 1962 and 1963, the latter of which saw Diefenbaker fall from power.

Pearson’s Johnson issue stemmed from an April 1965 speech in Philadelphia, which Johnson interpreted as a criticism of his Vietnam policy. One account of a subsequent Camp David encounter had Johnson angrily grabbing Pearson’s lapels and declaring: “You came to my living room and you pissed on my rug!”

By the mid-60s, Diefenbaker (born 1895) and Pearson (born 1897) came to be seen as fusty old men. Diefenbaker’s charisma was antiquated and Pearson had never been gifted that way. The go-go, swinging decade had no important place for such relics.

Diefenbaker went first, being unceremoniously dumped as party leader in 1967. And although he continued as a voluble parliamentarian until his death 12 years later, he had virtually no influence.

Pearson retired in 1968 and was largely ignored by his chosen successor, Pierre Trudeau. While he came to be privately critical of Trudeau’s foreign policy, he was a loyal party man and kept it to himself.

Politics is a brutal business.

Troy Media columnist Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps a little bit.

For interview requests, click here.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.