On the May 29, 1913, the Paris premiere of The Rite of Spring took place at the Theatre des Champs-Elysees. The Russian ballet’s choreographer was Vaslav Nijinsky and the symphony’s composer was Igor Stravinsky. Together that night, almost exactly 105 years ago, they unleashed a mad torrent of modernity on the members of Parisienne high society.

On the May 29, 1913, the Paris premiere of The Rite of Spring took place at the Theatre des Champs-Elysees. The Russian ballet’s choreographer was Vaslav Nijinsky and the symphony’s composer was Igor Stravinsky. Together that night, almost exactly 105 years ago, they unleashed a mad torrent of modernity on the members of Parisienne high society.

Lydia Sokolova was in Paris for the opening, and she was interviewed in 1965 about the event. “The audience didn’t even let the overture begin. As soon as it was known that the conductor was there, the uproar began.”

“There was an existing tremor in the air against Nijinsky before any curtain went up!” said Stephen Walsh, a noted professor of music at Cardiff University.

Apparently blows were exchanged, objects hurled at the stage and at least one person was challenged to a duel as Stravinsky’s strangled bassoon melody began during the opening section. The sounds in the theatre were truly unlike any the Parisienne patrons had ever heard.

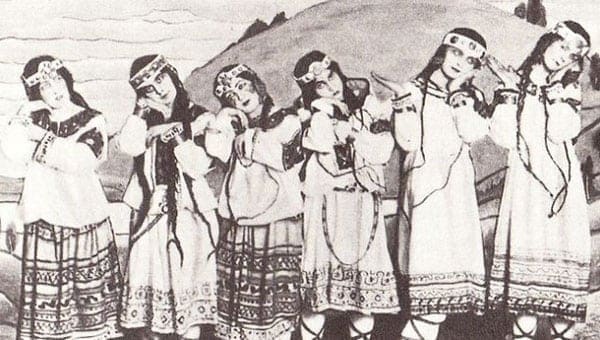

The dance was even more disturbing than the music – it invoked Russian primitivism and modernist chic simultaneously. Stravinsky characterized the dancers as, “A group of knock-kneed and long-braided Lolitas jumping up and down.”

Today the celebrated “Riot at the Rite” is acknowledged as one of the first very public gate-openings to modernism in Europe, and indeed to the 20th century.

Nijinsky and Stravinsky pitched tradition to the winds. Their actions played to a growing sense, certainly in Russia in 1913, of class warfare and impending revolution. While the audience that opening night was swathed in furs and diamonds, The Rite of Spring was directly appealing to the new, growing and increasingly enfranchised middle class. Through their small business incomes and public education, they were showing ‘society’ that they had the power to catalyze change in the artistic and aesthetic realms as well.

In Russia and generally in Europe, people were growing tired of the inherited privilege of tsars and kings. And they sought dissonant chords and pulsating rhythms in their lives.

Serge Diaghilev, founder of the Ballets Russes, famously asked Stravinsky of his opening score, “Will it last a very long time this way?” To which Stravinsky replied, “To the end, my dear.”

Esteban Buch, director of the School of Advanced Studies in Social Science in Paris, notes that what upset the opening night audience was, “the very notion of the primitive society being shown on the stage.” Nevertheless, The Rite of Spring concluded with an ovation of sorts, and chaos in the crowd as Stravinsky and Nijinsky took their bows.

People left the performance with a sense that they had been a part of an awakening.

Diaghilev told the Paris press that The Rite of Spring had caused “impassioned debate.” One account of the evening says that 40 people were arrested for their exuberant celebratory behaviour.

So how will Powell River, B.C., residents and Pacific Region International Summer Music Academy (PRISMA) guests react on Friday and Saturday, June 22 and 23 (at 7:30 p.m. and 1:30 p.m. respectively), in the Evergreen Theatre, some 105 years and 24 days later, when maestro Arthur Arnold conducts Le Sacre du Printemps (The Rite of Spring), arguably the gateway music of 20th century social reform?

If we are true to our town’s history, we will thrill to a performance that celebrates the open embrace of modernity, workers’ rights, the promotion of diversity and the acceptance of new technology.

In 1910, the Powell River Townsite was created on a parallel architectural template that set the Canadian stage for how remote industrial communities should embrace family values, the arts and grafts philosophy and the garden city design movement as core planning concepts.

One hundred and eight years later, Powell River is still supporting and advancing concepts that began in the original townsite.

In 1939, local millworkers secured the first B.C. Credit Unions Act charter with an opening deposit of $48.30. By 1955, First Credit Union had over 3,000 members and $1 million in assets. Today, it is the region’s lead financial player.

In 2004, Powell River was nationally designated a Cultural Capital of Canada for its arts and cultural program leadership.

The Tla’amin Final Agreement, which came into effect on April 5, 2016, set the stage for innovative First Nations government by the Tla’amin First Nation, the Indigenous leaders of local creative thinking. Their involvement as local government sponsors of PRISMA shows how reconciliation works amongst neighbouring communities.

Arguably, Powell River is exactly the kind of community that Nijinsky and Stravinsky would celebrate. Their choreography and composition nurtures the same roots, and feeds the same ambitions.

Troy Media columnist Mike Robinson has been CEO of three Canadian NGOs: the Arctic Institute of North America, the Glenbow Museum and the Bill Reid Gallery. He is also treasurer of PRISMA.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.